|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

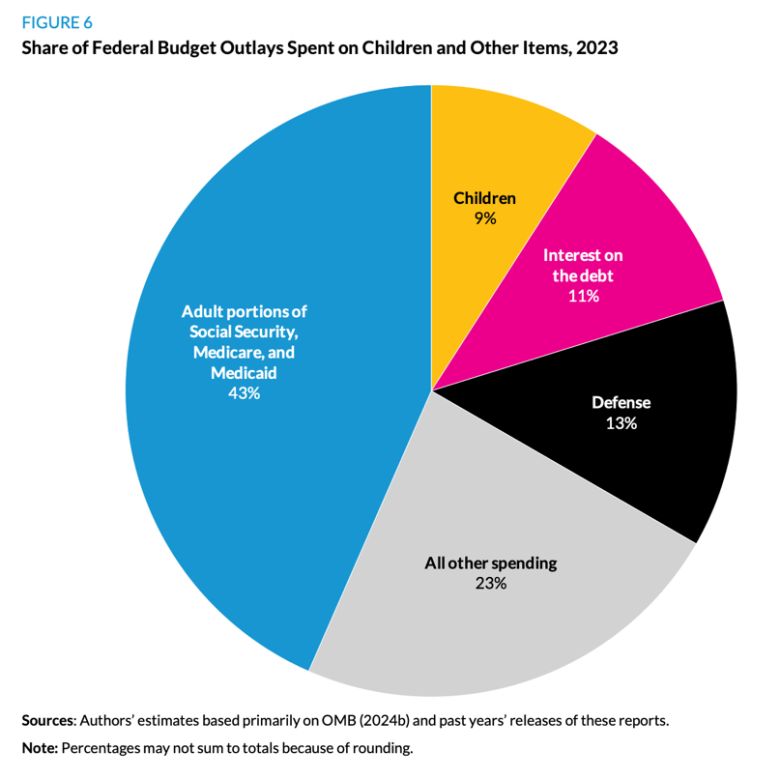

The government spends the equivalent of about $90,000 per U.S. household per year—yet many Americans don’t see the benefits. Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security and tax subsidies (primarily for wealthy households) swallow up the lion’s share of the federal budget every year, along with interest on the national debt.

All of this automatic spending means no room in the federal budget for investments in America’s future, argues budget expert Eugene Steuerle, while many Americans are losing out. In 2023, for instance, just nine percent of the federal budget went toward programs for children—while 11 percent was spent on interest on the debt. In 2024, the federal government spent $880 billion for interest on the debt, compared to $80 billion for the Department of Education.

In his new book, Abandoned: How Republicans and Democrats Deserted the Working Class, the Young and the American Dream, Steuerle blames a broken budget process that rewards short-term fixes and a Congress too polarized to tackle entitlement reform. He also argues that Republicans’ fixation on tax cuts has vastly contributed to inequality, while Democrats’ focus on consumption over investment has meant insufficient attention to helping working class Americans build wealth. The net result, Steuerle says, is a collapse in “fiscal democracy.” Increasingly, Americans are losing their stake in the federal spending as entitlements and debt consume the entirety—and then some—of the nation’s future budget.

Steuerle is the Richard B. Fisher chair at the Urban Institute, codirector of the Brookings-Urban Tax Policy Center, and the author of the Substack newsletter The Government We Deserve, in addition to 18 books.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. The full interview is available at Spotify, YouTube and iTunes.

***

Anne Kim: In your book, you argue that both parties are responsible for destroying opportunity in America. What sins have they committed together and what are the unique sins of each party?

Eugene Steuerle: Essentially, there have been two major dominant policy thrusts for almost a half a century, one by the Democrats and one by the Republicans. For Republicans, it’s largely been centered upon tax cuts. For the Democrats, it’s largely been putting money into retirement and Social Security and healthcare. And as a result of those two thrusts, almost everything else is getting shoved aside. Almost anything that promotes upward mobility really has gotten the short shrift for some time.

I’m not arguing that either one of those thrusts in and of itself is bad. It’s just that they’ve been so dominant they’ve squeezed out other important options we should be pursuing.

Anne Kim: If I understand your argument, you’re saying that as a result of Republicans’ prioritization of tax cuts, what’s happened is a widening of inequality, and that has limited mobility. And then on the Democratic side, the emphasis has been largely on consumption versus investment, and that has further squeezed mobility for the groups you lay out in your book, including young people and the working class. Is that roughly correct?

Eugene Steuerle: That’s exactly right.

Education is an easy example. We’ve failed on a lot of fronts on education. Quite honestly, to get quality teachers, you have to pay for them. To get quality teachers in early childhood education, you have to pay for them. We pay very little for that. We’ve also neglected for a long time young people who don’t go on to college. We don’t have much of an apprenticeship program in this country. We have to figure out ways to put money into those of efforts.

I also suggest very strongly that we should be doing a lot more in the way of wage subsidies. All these efforts at picking particular industries we’re going to favor or tariff do very little for the working class. So I argue that we ought to be beefing up a lot the work subsidies we have in this system. I even suggest perhaps something like a universal basic wage—not basic income, because I think that’s a mistake.

The current earned income credit mainly goes to single mothers with children, whom we want to help, but it’s left out a lot of the people you’ve written about yourself, like young males, young people in general, who feel left out of the system because in fact they’re not eligible for those types of subsidies. And married couples who have two earners, they get phased out of a lot of systems. There’s a huge marriage penalty throughout our subsidies.

And on the financial side, our pension subsidies mainly go to people who have good incomes because it’s proportional to the amount of money you can put in the system. And housing subsidies like the home mortgage interest deduction have done really nothing to expand home ownership for some time. We could do much more to help first time home buyers and not people like me who already own a home and don’t need the extra subsidies.

All these things are the items that would promote upward mobility, and they’re the things that are getting squeezed and put aside.

Anne Kim: You’ve begun to answer this question about how current policies are betraying the people who most need the help. But could we talk a little bit more about the ways in which current budget policy and current domestic policy betray the young? You’ve begun to talk about that in terms of what we’re failing in far as education, but what are some other things you point out in your book about how we’re really betraying what we owe future generations because of the way the budget has been set up?

Eugene Steuerle: The young are among those groups who are being squeezed out by these programs. About 20 years ago, almost now, I started a series at the Urban Institute that you’re aware of called KidsShare that tries to track the budget for children. The budget for children is very, very small.

I want to be clear I’m making a relative argument. We spend huge amounts on people my age. A typical elderly couple retiring today gets about $1.3 million in Social Security and Medicare benefits. Millennials are scheduled to get about $2.5 million dollars because ofall the built-in growth in those programs. Well, that’s being done instead of putting money into education for children, or work subsidies for workers, or anything else along those lines.

It’s this squeezing out of these programs more than an outright rejection of them that’s been happening. The programs for children and workers for the most part don’t really grow over time, whereas programs like healthcare and retirement have all this automatic growth built into them.

Both political parties in the last election said they really care about the working class. And I’m saying, “Hey, guys and gals, get around to proving it.”

I’m not arguing we shouldn’t have social security. Social Security is probably the most successful program we’ve had in this country. I’m not arguing we shouldn’t have health care, in fact, we need more universal health care. I am arguing we shouldn’t automatically be spending ever larger portions of our economy on health care and on extra years of retirement in preference to other efforts.

Anne Kim: On the solution side, you talk about something you call “fiscal democracy.” What does that mean and how do you suggest going about achieving that?

Eugene Steuerle: One of the measures I’ve developed over time with Tim Roper is an index of “fiscal democracy.” We measure the share of revenues that are left after you take into account what’s called mandated spending—entitlement spending, or the spending that’s automatic.

Social security grows automatically through a variety of factors. Healthcare grows automatically because prices are often set by producers, such as drug companies.

The revenues that are left after you take into account that spending is actually to zero. All revenues are already committed to those items. So if you could think about it this way, everything else in the aggregate is paid for out of deficits, and the mandated spending is still growing faster than our revenues.

So that number, that index of fiscal democracy, is scheduled to go well below zero. Now mind you, in the ’60s, 60 percent or 70 percent of our spending was discretionary. It wasn’t mandated. Congress would go in and decide each year what to do. Even in the Clinton years, the number was closer to maybe 30 percent.

This lack of fiscal democracy explains to a great extent why Congress over the last couple of decades has been unable to get a hold of the budget. If mandated spending is scheduled to grow faster than revenues, and that’s not sustainable, then the job of Congress is not to decide what to do with the new revenues but to renege on past promises. And reneging on past promises is a clear way to lose the next election. Both parties have been scared to death to lead or even unite to deal with these issues.

The whole culture war, in my view, has been a replacement for the budget policy that is the main job of government. And by budget policy, I don’t mean just the dollars, I’m talking about administering programs and running programs. That’s the main job of government. We’re fighting over which kids can go to which bathrooms. That’s not a legitimate issue.

We’re fighting over things where government has limited control as opposed to things they do have control over. We lack fiscal democracy, and I think it’s a threat not just to the economy, it’s a threat to democracy itself because it’s now very hard for each new generation of voters to feel they’ve got control over what happens.

The Democrats don’t want the Republicans to come in and have another tax cut, but the Republicans don’t want the Democrats to come in and be able to spend more. So they go through this constant battle about trying to stop the other party from doing what it wants, but they are not willing to cut back on what they have done to excess.

Anne Kim: How do you suggest breaking through this short-term thinking? For better for worse, as long as our constitutional system is the way it is, we are trapped with two year cycles in the House and the six year cycles and the four year cycles for the presidency. But you’re talking about changes that require a Congress to think 20, 30, 40 years in the future. How do you reconcile the political realities with the fiscal realities that have to be grappled with at some point?

Eugene Steuerle: This is very difficult right now. I love Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s statement about “defining deviancy down.” I think we’ve actually become more deviant in our policy and our policy discussions, so I don’t see any immediate end to that. I think at some point things crash.

Hopefully, they don’t crash economically. Hopefully, they crash because the public finally decides it really is tired of all this and demands something. So we voters are not totally innocent from what’s going on. We vote for people who often try to mislead us.

I think it’s going to take some real efforts at bipartisanship in Congress and maybe us voters voting for people who can work across the aisle. But I do not have an easy political answer.

I do think that the way budget people like myself present the data to the public is often misleading. I’ll give you one example. When we do a tax cut, typically, we do a distributional table about the winners: Here’s who got a tax cut. Well, that’s misleading because somebody’s paying for it.

The people who have to pay the bill down the road—we don’t know how to identify them. So we don’t show them. But the result of that presentation is that it makes it appear that a tax cut or a spending increase does good, and a tax increase and a spending cut does bad.

Anne Kim: We recently reached $38 trillion on the national debt, which is the highest it’s ever been. Both parties have been guilty of arguing that deficits don’t matter. For a brief, Modern Monetary Theory was taking center stage on the left, and the GOP has actually never considered deficits to be that big of a problem starting with Ronald Reagan. What’s your argument that deficits actually do matter and that we’re going to start seeing the impacts of this kind of debt fairly soon?

Eugene Steuerle: In fact, we are starting to see one impact in just the last two or three years, which is that interest costs have been rising as a share of GDP and rising fairly rapidly.

From 1980 to about 2020, the debt to GDP ratio quadrupled from about 25 percent of GDP to 100 percent of GDP. The Social Security and Medicare Trust Fund imbalances that we’ve long predicted are now within a 10-year cycle.

I think members of Congress are well aware of these things happening. They just don’t have the wherewithal, in some cases the courage and the processes in place to actually try to deal with it. And we’re having this cultural war that totally sidetracks us.

Anne Kim: So do you have advice in the short term for politicians who are looking at all of this about anything small that they could do? Assuming that the House comes back into session at some point and Congress is functional—or let’s just say it’s 2026, and there is some balance of power restored to Congress. What’s the first thing that Congress should think about doing to restore the fiscal democracy index to a level that is more sustainable for the nation?

Eugene Steuerle: Well, they could certainly enact budgets that try to start tackling the problem. I fear that the issue is so widespread that the good or the right ways to do it can’t happen in the short run.

But nonetheless, they could start doing something. Anything that moves a little bit in the right direction is better than something that moves in the wrong direction, like the recent budget bill.

David Walker, Former Comptroller General and head of the Peterson Foundation always said, “When you’re in a hole, don’t dig deeper.” So that’s a one little thing.

Something I think that Congress could do that I’ve been arguing for 40 years is to address a lot of the weaknesses of a lot of programs by simply making what I’ll call deficit neutral tradeoffs.

I’ll give you one little example. Congress recently adopted a new charitable deduction that for reasons I won’t fully get into is really fairly badly designed to promote charitable giving.

Well, let’s create a better charitable deduction. If we don’t want to have to fight over the size or the revenue or whether government’s bigger or smaller, let’s just make it more efficient.

And then finally, if you really want to do something much bigger, you could do things like decide that in Social Security, you’re going to stop wage indexing of benefits as long as the system is out of balance. I would probably stop it only for higher income people, but it’s a part of every Social Security plan that’s out there. There’s no way that Social Security is going to continue to promise higher-income Millennials the benefit it now suggests.

You could also put much better caps on healthcare spending. There’s almost no part of our federal subsidies for healthcare, which cover about two thirds of all healthcare spending, that’s adequately capped or limited.

Congress is always going to want to do more and more. But if you get the long run in control, it’s a lot easier to deal with the short run. If the long run is out of control, then you just make short-term fixes and you’re still always in the soup.